Recruiters have always had to sift out embellished CVs. But why do HR professionals fall for fake degrees, and what can they do to guard against a dishonest applicant?

“Tim* wasn’t an amazing performer, but he’d joined our HR team as a short-term contractor via an agency, and they claimed to mirror our background checking requirements. He claimed to be CIPD qualified and to have a first-class degree from the University of Bristol. As an alumnus myself, he didn’t strike me as ‘typical Bristol student’ – something I often joked about with him.

“The day after Tim’s contract ended, we received an anonymous phone call from someone telling us to Google him. We were shocked to discover he’d been convicted for fraudulent qualifications before working with us. On reflection, maybe we should have been suspicious: a junior member of our team later told me she’d seen him Google how to hold a disciplinary meeting. There were a couple of other things he’d been pulled up for not doing properly, but he’d talked his way out of them.”

Samantha* is just one of many HR professionals who has been caught out by employees’ fraudulent claims of degrees and other professional qualifications. In January 2018, an investigation by the BBC’s File on Four programme found that more than 3,000 fake qualifications were sold to UK-based buyers by a single company in 2013 and 2014, with one British buyer spending nearly half a million pounds on fake documents such as master’s degrees and doctorates.

CV embellishment is far from a new or uncommon phenomenon – 80% of 5,000 CVs analysed by the Risk Advisory Group in 2017 were found to have at least one discrepancy – but the internet is making it easier than ever for candidates to obtain fake qualifications. But, with only 20% of UK employers carrying out proper checks through the Higher Education Degree Datacheck (HEDD), is the problem growing? And how can HR professionals respond to the threat that fraudulent claims pose to their organisation?

A significant contributor to the growth in fake qualifications is that more and more employers are requiring candidates to have degrees for jobs that don’t really need the qualification, argues Charlie Ryan, managing director at The Recruitment Queen. “In the last 10 years, we often told our young workers that we wanted a degree no matter what else they had to offer. In many cases the degree wasn’t necessary, and once they were in the door, whether they had it or not was irrelevant. If the degree really is required then, with the right interview process, it will become apparent very quickly that the candidate doesn’t have the knowledge.”

“It’s almost become the acceptable norm that candidates believe changing their CVs is ok,” says Matthew Armstrong, managing director of background checking firm Giant Screening. “Employment application fraud is one of the few types of fraud that is rising; data from CIFAS shows that successful cases rose nearly 15% in 2016 compared with 2015.”

The risks of employing an individual with a falsified CV are “significant and wide ranging,” adds Armstrong. “Often employers seem to think that their senior hires pose the greatest risk to the business, but this simply isn’t the case; the majority of internal fraud is committed by people aged between 21 and 30, for example. Employers could lose business, suffer brand damage or face legal challenges because of a bad hiring decision.”

The reputational impact is becoming increasingly important as more cases are finding their way to the courts. In 2010, Rhiannon McKay was convicted of CV fraud and sentenced to six months’ in prison after falsely claiming to have two A-levels and forging a letter of recommendation. In 2017, Jon Andrewes was sentenced to two years in prison after falsifying his qualifications to secure a job as a senior NHS manager.

These lies could have been picked up by background checks, but many employers choose not to carry them out. “It could be that they don’t see the risk that employing the wrong person could pose to their business, they believe they can sense when a person is being dishonest, or they perceive the time it takes to carry out these checks as better spent on other activities,” says Armstrong.

“Checking qualifications today is cheaper, quicker and generally easier than it has ever been,” adds Tony Vieira, a solicitor at FPG Solicitors. “There are numerous companies that can check prospective employees’ qualifications in just a few days. HEDD will check higher-education qualifications, professional qualifications can be checked with the awarding institution, and you can even check attendance at secondary schools using Experian.”

The most important things to remember, says Vieira, are “to be consistent, and to always tell the employee that you will be carrying out the pre employment checks, and that any offer of employment will be conditional on the results of the enquiries being satisfactory. You have to be consistent so you are not accused of being discriminatory, and at risk of an employment tribunal claim. You must tell candidates about the checks in advance, so they can provide you with express consent for carrying them out.”

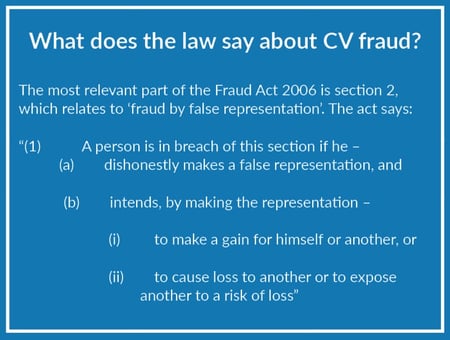

An employer who uncovers an instance of a fraudulent degree isn’t legally obliged to report the matter to the police, says Vieira, “but the moral position may be different. The police are only interested in criminal offences and, while obtaining, or attempting to obtain, a role by fraudulently misrepresenting one’s qualifications is technically an offence under the Fraud Act 2006, in reality, very little – if anything – will be done.

“In practice, where a qualification is not required for a particular role, that is, where it is not a professional qualification but rather a preference imposed by the employer, then the likely effect of qualifications fraud is likely to be limited to a poor performing and dishonest employee,” he says.

For Ryan, in such cases “the biggest concern here isn’t the qualification – it’s the dishonesty. Trust is crucial to the success of a relationship. Lying when I have enquired or questioned, would lead me into serious doubt as to what else they would lie about.”

HEDD’s recommendations for employers include writing and distributing a policy on fraudulent qualifications; that background checks be made a standard part of the hiring process; and that employers not only act against those who commit degree fraud, but also record and share evidence of fraud with bodies such as the HEDD itself.

Vieira says HR can take on some of the ‘detective work’ themselves by searching social media profiles, and asking probing questions about a candidate’s degree – such as the names of modules and lecturers – at the interview stage. But, he adds, the work doesn’t end when a candidate is hired: “This should be an ongoing process. Even once the person has been employed for a period of time, employers should look out for any inconsistencies in the employee’s history. Those who have declared false qualifications tend to let their guard down once they have their feet under the table. It is always preferable to find out and take action before any damage or losses are caused to your organisation.”

For Samantha, it’s certainly a case of ‘once bitten, twice shy’. “The experience has definitely made me more cautious around checking documents relating to both educational and professional qualifications,” she says. “Before this incident, I never checked professional membership with the awarding body – but I do now if there is cause to be concerned.”

* Names and other details have been changed to protect identities